Drought Subsides, but Dry Summer Likely

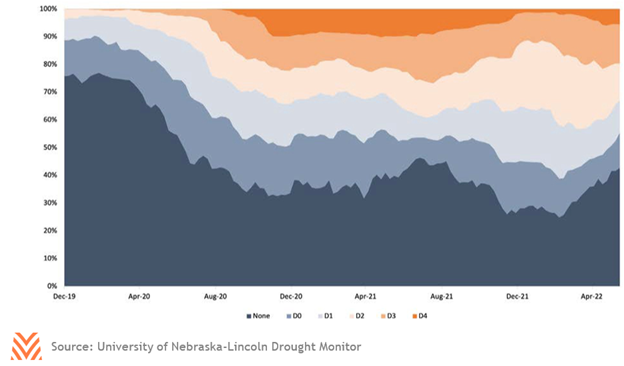

In late April, drought conditions across the West Coast were becoming ubiquitous. More land was in some stage of dryness or drought than at any point since 2012. These conditions were concentrated along the West Coast, Mountain States, and Plains states. National pasture, winter wheat, and sorghum conditions were at historic lows. National conditions have seen modest improvements since. The figure below shows national drought conditions through the middle of June. The sweeping drought covering much of the country has given way to smaller but more severe pockets of extreme drought in parts of Texas, New Mexico, and California.

The U.S. has had many cycles of dry weather in the past. Both the 2002 and 2012 droughts led to significant impacts on U.S. production. What is unique about the current period is both the duration and severity of that dryness. Of the 100 weeks with the most severe drought since 2000, 42 were in 2021. June 2022 marked a year and a half with at least 10% of the country experiencing at least category D3 extreme drought, the longest period since 2000. While many producers will experience no water access challenges in 2022, those who do have experienced both longer periods and more severe periods of drought than many recent droughts.

One of the contributing factors to this period of dryness is the current La Niña weather event. The national Climate Prediction Center’s June forecast found that there was a 52% chance that the event would persist through the summer and an even greater chance of it persisting through the winter. While La Niña events typically last less than 12 months, the current pattern has already persisted for 20 months. The extreme drought currently seen in Texas and the Southwest is the exact pattern of dryness expected from a La Niña event, and its persistence through the summer could signal difficult growing conditions for producers in those regions.

Compounding these problems are rising challenges for both surface and subsurface water availability for producers across the country. While California producers have experienced restrictions for years due to the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, water access is likely to become a greater challenge for producers across the country. One study from the U.S. Geological Survey found that the Ogallala aquifer, which supplies water to eight Plains states, has seen water levels fall by as much as 150 feet since the aquifer was first tapped in 1950. Those declines have continued in recent years, with entities like the High Plains Water District in Northern Texas finding a decline of 0.63 feet between 2021 and 2022.

These declines are likely to lead to restrictions for producers across the country in the coming years. In Nebraska, the state government invoked an interstate compact that allowed them to divert water from eastern Colorado in a plan that cost approximately half a billion dollars. In southern Georgia, a Florida legal challenge could have put water usage restrictions to ensure that sufficient water flowed downstream. And although that case was won in Georgia’s favor, downstream water rights have also been the subject of Supreme Court lawsuits in just the last decade between Montana and Wyoming, Texas and New Mexico, and Kansas and Nebraska. The increasing frequency of these cases poses additional risks to producers who may become subject to water restrictions resulting from select decisions.

For now, the worst of the 2022 drought is over for many regions. Select pockets of drought remain in the Southwest and Texas, and those regions are likely to see continued water shortages due to the persistent La Niña pattern. That same pattern has helped and should continue to alleviate water shortages in the Northern Plains. Midwest producers are likely to see wetter conditions at the end of the growing season. But producers, especially those in the Southwest and Plains, should be cognizant of potential water restrictions coming out of court cases in the coming years.