How to stay ahead of a downturn

FarmFutures

By: Ben Potter

It was 1983, and the timing couldn’t have been worse for first-generation Indiana farmer Randy Kron to kick off his career. Commodity prices were dismal, interest rates had spiked by double digits, and the U.S. economy was clawing its way out of a three-year recession.

The deck wasn’t totally stacked against Kron, however. A frugal attitude and a bit of good fortune with an unconventional crop helped him even the odds. By growing white corn — a mainstay used for tortilla chips and other popular foods — Kron was able to fetch a premium and slowly grow his operation from 66 acres nearly 40 years ago to around 2,100 acres today.

“White corn got us through the 1980s,” Kron says. “It also made us pay attention to every penny and made us better managers. We’re still trying to figure out what the new ‘white corn’ is.”

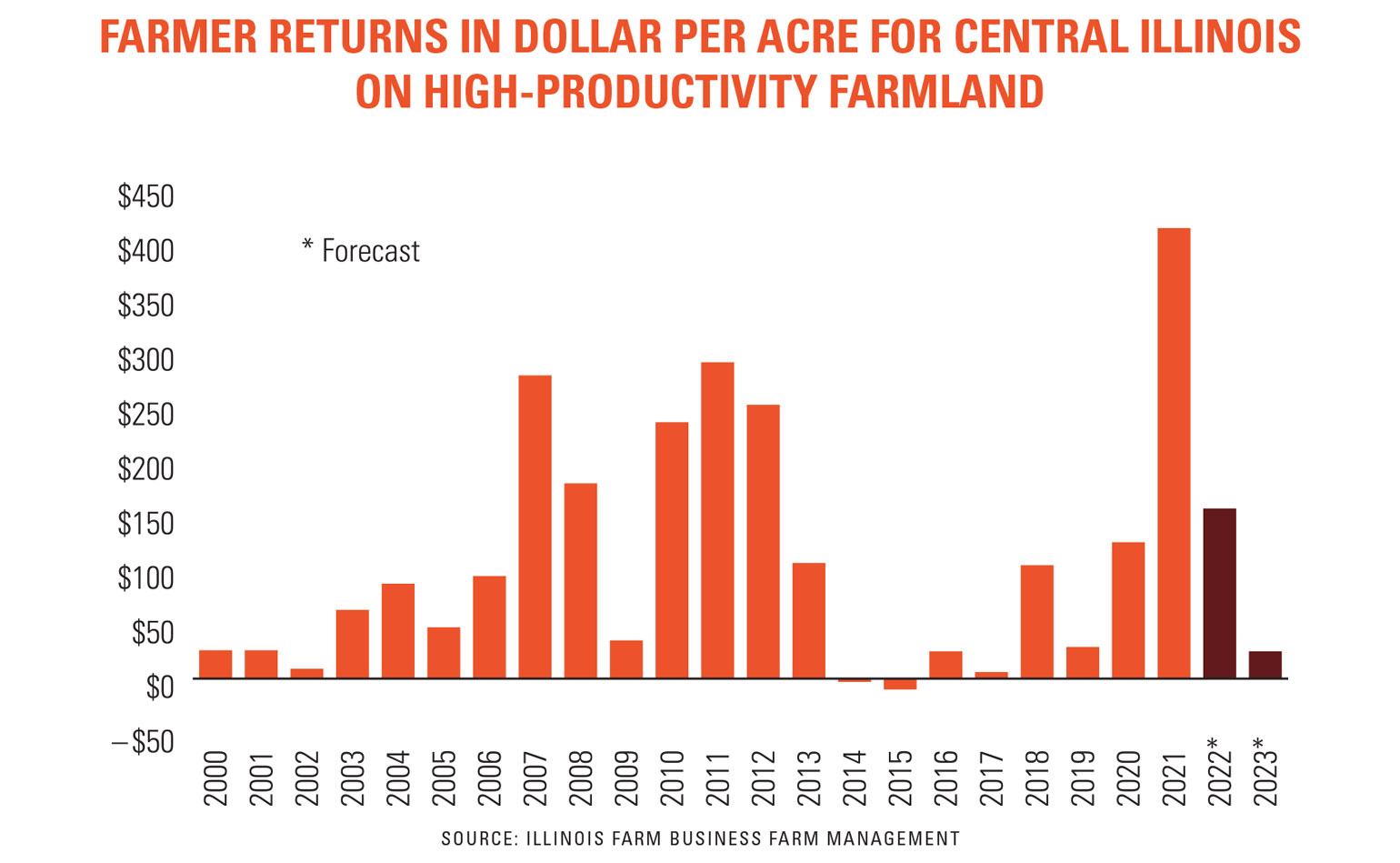

Kron and his son, Ben, are also trying to figure out how to build a bridge from the past two profitable seasons into a more uncertain 2023. They’ve been asking the same question that has been on most farmers’ minds: What should we do to prepare for a potential downturn in prices?

Look at leverage

Farmers who made it through the 1980s remain wary. Will history soon repeat itself with another severe downcycle? But Jackson Takach, chief economist with Farmer Mac, is optimistic that current circumstances aren’t conducive to producing a sequel. In part, that’s because historically low interest rates led to a wave of refinances in 2020 and 2021.

“More farmers are in long-term fixed, record-low interest rates; there are record low defaults; and banks have high liquidity right now,” he says. “We’re in a much better position to bridge to the future.”

For those who haven’t refinanced recently and are still interested in doing so, contact your lender. Just proceed with caution, according to Zachary Carpenter, chief business officer at Farmer Mac.

“You always need to read the fine print, and be sure to ask if there are prepay penalties,” he says. “Optionality is critical.”

What is optionality, exactly? As the word implies, it has to do with the amount of options a particular loan provides. In other words, what are the “different allowable courses of action” available? At minimum, you should know if your loan has early payment penalties. If it’s a variable-rate loan, it’s also worth knowing the details on how and when those rates may adjust.

“Just know the details,” Carpenter advises. “The details can sometimes be costly. And as we see uncertainty and volatility, lenders like to see producers focus on interest rate risk and overall leverage.”

Is this a good time to parlay current profits into farm expansion? It’s hard to take emotion out of these decisions, Takach notes, especially for those so-called “once in a generation” farmland sales. But try to list out pros and cons, such as price point, proximity and productivity potential.

“You still have to do the math to make a logical decision because you’ll be living with that decision for a long time,” he says. “But I get it. It’s difficult to turn your back if a rare opportunity presents itself.”

Alternative revenue

Just as white corn carried the Kron farm through the 1980s, farmers should always be on the lookout for possible alternative revenue streams.

Hemp held the most hype a few years ago, but that has largely died down. Carbon markets appear to be the next big thing, and green energy companies continue to make the rounds, trying to lure landowners into converting cropland into rows of solar panels or wind turbines.

“There are a lot more opportunities coming that will look more attractive when corn is at $4,” Takach says.

When it comes to carbon capture revenue, Kron has been content to wait in the wings for now.

“We need to sort out what’s the right value and if it’s a net value for our bottom line,” he says. “It also has to be sustainable for the pocketbook.”

Large-scale solar projects have become a sore subject for some rural communities. Although profits can be lucrative, it also can tie up a piece of land for 20 or 30 years. On rangeland, it’s more of a no-brainer — cattle can graze among the panels and even enjoy the newfound shade they provide. But converting cropland is a much more contentious proposition. Great Plains Institute concedes the top three concerns for solar development are:

- The impact on agricultural production.

- The effect on local and regional natural resources (soil, groundwater, habitat, etc.).

- Change in community character (chance of being an eyesore).

But with a lot of potential alternative revenue on the line, these projects can’t be dismissed without at least giving them a little thought. It may also pay to mine for possible dollars from various governmental grants and programs. Look for alternative ways to increase revenue or reduce costs — sourcing manure for fertilizer is one example.

“The good news is you still have some lead time to think through some of these options,” Takach says. “Planning ahead cannot be understated.”

Run the numbers

Volatility has been a mainstay of the 2022 season. Both input costs and commodity prices have fluctuated dramatically throughout the year. That has farmers like J.D. Burns keeping their head on a swivel.

Burns, who farms around 1,100 acres of corn and soybeans with his father in western Kentucky, says he often reviews his crop budget as much as every couple of weeks.

“I always like to know where I’m at,” he says. “I try to budget accordingly, and I run worst-case scenarios because I know how each field performs in good years and bad years. I don’t want to spend what I don’t have.”

Burns adds that it’s too early to tell if he’ll make rotational changes for 2023. Input prices are historically high, but he says it doesn’t make sense to skimp on anything that could negatively affect yields.

“Inputs are expensive, but the prices are there to still be very profitable,” he says.

Steve Isaacs, Extension farm management specialist with the University of Kentucky, recommends breaking down farm financials to the field level, something he refers to as an enterprise budget.

“What is each enterprise doing for me?” he says. “How well is each component doing?”

Isaacs also suggests that farmers remember what’s in — and out — of their control. And then respond accordingly.

“Farmers are notoriously interested in circles of concern but not circles of influence,” he says. “You can’t influence the weather, for example, but you can influence your budget.”

Capital investments

Both Burns and Kron say they will take a conservative approach to making equipment upgrades in the near future. Supply chain issues may make those decisions even more difficult.

“We’ve been talking about a planter upgrade, but I’m not even sure if we’ll be able to find it,” Kron says. “Some of that’s on hold because it’s not a choice.”

Still, Kron tries to make periodic equipment upgrades to stagger operational needs.

“It can get away from you to where everything’s old and everything needs to be updated [at once],” he says. “We’ve always had the philosophy of trying to upgrade a little bit at a time. But it’s looking like 2023 could be a pretty lean year, so we’re on the conservative side in terms of capital expenditures.”

Burns predicts 2023 will bring its own unique set of trials to conquer. But he says his time spent in the U.S. Marine Corps gave him the attitude and discipline to face them head-on.

“What I love about farming is there’s always a new goal, a new challenge, a new day,” he says. “There’s always something to work toward.”

To view the full article, click here.