An Unprecedented Cycle in Almond Prices?

Almond producers have endured some significant headwinds over the past five years. During the COVID-19 pandemic, port backlogs slowed or prevented millions of pounds of almond exports. Then, as logistical challenges eased, the Federal Reserve began sharply tightening monetary policy in 2022 to combat rising domestic inflation. This led to sharply higher borrowing costs for producers. Moreover, water supplies have remained at the forefront of many minds since the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) was signed into law in 2014. Coincidentally, the first major implementation milestone in 2020 coincided with one of the worst droughts in California over the last century.

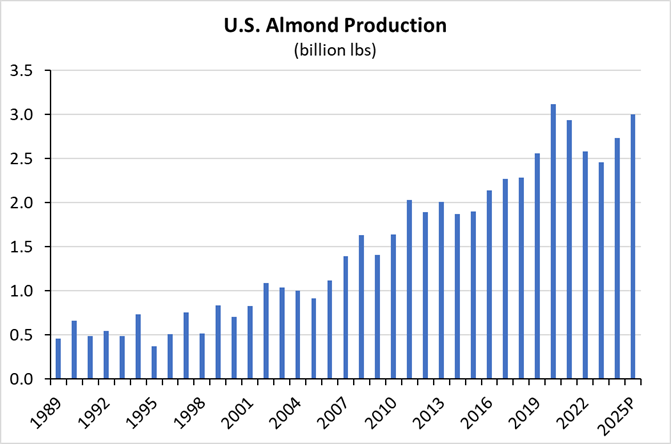

While these difficulties alone might have been tricky to navigate, the decline in producer almond prices over this period has perhaps been the most difficult challenge of all. Almond prices peaked at $4.00 per pound in 2014, according to the USDA, the highest level on record. Encouraged by strong prices and rising global demand, producers and investors planted tens of thousands of new acres. However, these newly planted trees have come into production in an entirely different price environment, with almond grower prices dropping to $2.45 per pound by 2019 and reaching a bottom of $1.40 per pound in 2022.

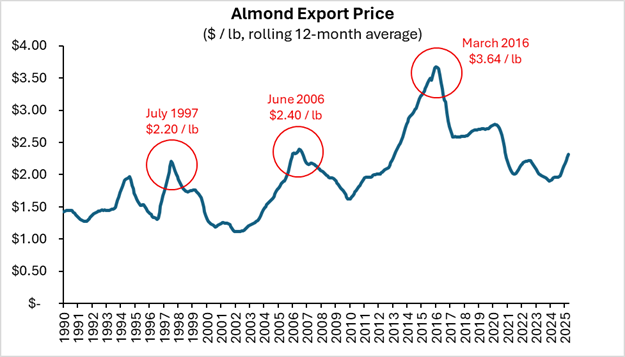

The reality is that cycles for almond prices, like many other agricultural prices, are nothing new. Over the last 35 years, almond prices have experienced at least three different cycles of sharp increases followed by several consecutive years of declines. Each cycle began with optimism, followed by periods of financial stress.

What Drives These Cycles?

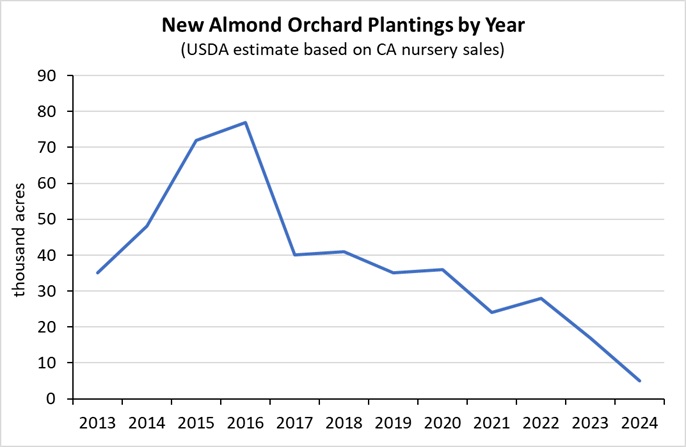

While each cycle has its own unique set of causes, a recurring theme is the imbalance between supply and demand. Price spikes often trigger a surge in tree plantings as producers respond to high prices. New almond plantings in the five years following the previous three price peaks were approximately 41% greater in total than the total plantings in the five years leading up to the peak. For almonds (and other tree nuts), these new plantings do not start bearing fruit until several years after planting. Once they begin bearing almonds, though, the increased supply may have tipped the scales in favor of buyers and put significant downward pressure on prices.

A crucial point to consider: Increased plantings do not necessarily equate to higher production. In fact, the biggest driver of the previous three price spikes was an unexpected drop in production, despite bearing almond acreage trending consistently higher from the 1990s into the 2020s. U.S. almond production dropped 49% in 1995, 9% in 2005, and 7% in 2014. Each decline was due to numerous factors, but the end result was tight almond supplies over the following year and higher prices.

New Almond Plantings Evaporate

As in previous cycles, new almond acre plantings have slowed in response to declining prices—but this time, the drop is more drastic than the previous two. USDA estimates show new almond orchard plantings dropped to approximately 5,000 acres from June 2023 through May 2024 (the most recent estimate available). Planting levels this low are exceeded by the number of acres being pulled from production due to aging trees. As such, total California almond acreage declined for the last three years for which data exists—a trend not seen in nearly 30 years ago.

Several factors are exacerbating the decline in planting this cycle relative to the last two. Prices falling by upwards of 50% or more have undoubtedly been a strong factor. Rising interest rates have also caused the economics of new potential orchards to be extremely challenging. Borrowing costs have more than doubled for some agricultural loan types over the last five years, causing the upfront costs to swell when considering that new almond plantings take years before generating revenue.

Beyond simple economics, water uncertainty adds another layer of complexity. Nearly all U.S. almond plantings are in California, with most of the orchards concentrated in the Central Valley. Producers in this region continue to navigate the implementation of the 2014 Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA). SGMA was, among other things, intended to regulate groundwater pumping in California. The rollout and implementation of this law, including the reduction of water allocations, have led to significant uncertainty for growers in some areas. Furthermore, increased monitoring of groundwater levels in the region has since revealed that some farmland is sinking as groundwater is pumped out. This phenomenon is called subsidence, and it likely further complicates the rollout and adoption of SGMA. Without a clear understanding of future water availability for some fields, many producers have chosen to fallow ground or reduce plantings when almond orchards reach the end of their useful life.

Outlook - Waiting on the Next Peak in Almond Prices

The USDA forecasts almond production will reach three billion pounds in 2025, a 10% increase from 2024 if realized. While this would mark a relatively large increase, the jump is not entirely unexpected. Market participants may have predicted this size crop using average yields and the current bearing acreage. In fact, the forecast yield per acre is still lower than five of the last ten years, highlighting that the jump in production is due largely to the increase in almond bearing acreage. Encouragingly, strong demand for last year’s crop will likely reduce carryover inventory, potentially supporting almond prices from the start of the 2025 almond crop.

Whether almond prices continue to rise in the years ahead remains to be seen. Long-term fundamentals remain strong for almond consumption globally as the middle class continues to grow and diets evolve. U.S. domestic consumption has been robust, and exports present a significant growth opportunity, especially as agriculture remains a key topic in trade negotiations.