Cattle and Hogs

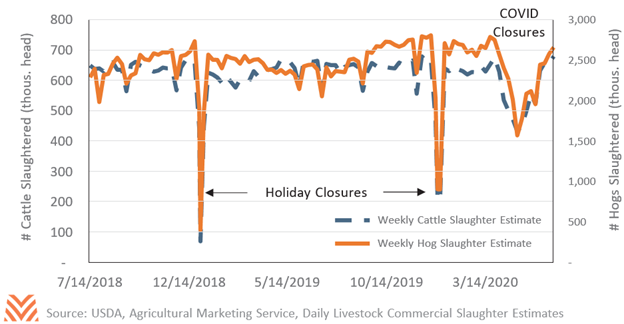

Demand for cattle and hogs saw considerable volatility in the second quarter of this year. COVID-19 outbreaks roiled the meat-processing industry throughout April and May. The close nature of the packing work combined with the cold, damp environment inside the plants increased the person-to-person spread of the novel coronavirus. In counties with a high number or percentage of employees working in food processing plants, the number of reported COVID-19 cases increased by 470% between April 1 and April 30, compared to other counties with an increase of 370% in the same period. COVID-19-related deaths increased 14-fold in the same time frame and counties, compared to 11-fold in other counties. More than 40 individual processing plants temporarily closed in April and May to allow employees to isolate and quarantine as well as to enhance plant personnel safety protocols. Some of the plants that closed were very large, such as the Tyson Foods pork plant in Waterloo, Iowa (3,000 employees, nearly 20,000 hog-per-day capacity), and the Cargill beef plant in Schuyler, Nebraska (2,200 employees and 4,500 cattle-per-day capacity). By May 2, U.S. beef processing stood at 69% of capacity, and U.S. pork processing stood at 60% of capacity (see the figure below). On April 28, President Trump signed an executive order under the Defense Production Act declaring these plants part of the country’s critical infrastructure, reducing liability for packers and processors. Plants with high positive test rates sent employees home to heal, and many installed additional protective equipment to help prevent future spread; by June 20, industry capacity had returned to full output.

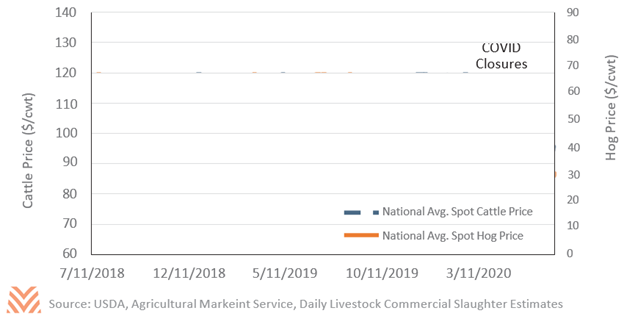

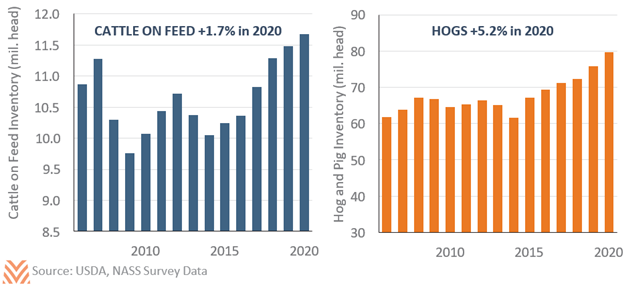

Although the return of meat processing capacity happened faster than many expected, the 40% decline in production took its toll on cattle and hog operations. With fewer buyers of live animals, inventories of both cattle and hogs increased significantly. Hog producers were hit particularly hard, as the pork production lifecycle is only around six months. The hogs that were meant for market but went unsold in May remained on farms and in barns, causing crowded conditions for the next litter. Overcrowding created sharp oversupply, and many producers were forced to kill animals on- farm with no place to send mature hogs. This issue was exacerbated by the recent expansion of pork production in the U.S., with hog inventories up 30% in the last five years. Between March and April of 2020, cash hog prices fell more than 30%. Because the cattle cycle is three to four times as long, overcrowding was less of an issue. But the drop in cattle buying certainly affected prices with a decline of 11% between March and April 2020 (see the figure below). While cattle prices rebounded somewhat in May, hog prices continued to drop, as animal oversupply is an issue that is not easily or quickly corrected. More than 3.7 million hogs went unprocessed in May 2020, and even if the industry operated continuously at 105% of capacity, it would take another six to eight months to work through the backlog.

Demand will drive the other half of the livestock pricing equation. Beef and pork demand have remained elevated, particularly at domestic grocers. Processors have been able to ink healthy margins as a result of higher retail pork and beef prices. Pork exports to China slowed in June, but cumulative pork exports for the year are up more than 30% compared to 2019. Domestic demand for beef has held up during the pandemic, but there is some cause for concern that away-from-home dining will not return to pre-pandemic levels this year. Beef demand would also be impacted by a prolonged global recession, as there is a strong linkage between beef consumption and rising income levels. Cattle futures prices in early July show levels holding at $105 per hundredweight into mid-2021, evidence that there is some stability returning to cattle prices. Lean hog futures are flat at current levels through the end of 2020, with a sharp rebound in the first half of 2021. This price trajectory fits with a narrative of backlog reductions in 2020, followed by a more normal production environment in 2021. However, through early July, COVID-19 cases are building once again in counties that have food processing plants. Another round of plant closures could cause volatility to extend into 2021.