Changing Conditions of Farm Bankruptcies

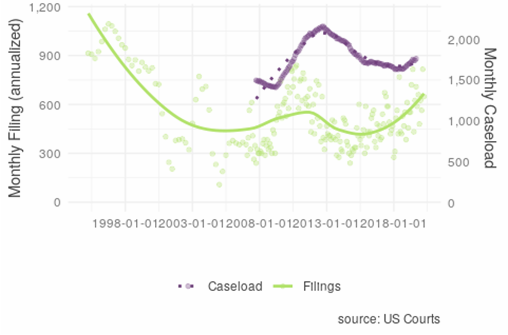

A continued lower-price environment, uncooperative weather events over the past year, trade uncertainty, and COVID-19 have all contributed to depressed net cash farm income levels and placed upward pressure on farm bankruptcies. Some of the lower net cash farm income has been offset by government payments; however, there is still significant financial stress in the agricultural sector. The U.S. Courts recently released the bankruptcy filing numbers for the first quarter of 2020, which had a total of 170 chapter 12 bankruptcies filed, an increase from the previous year’s first quarter of 130 chapter 12 bankruptcy filings. This increase came even though the COVID-19 pandemic delayed in-person events at bankruptcy courts, which suppressed the number of filings in March. Since 2014, chapter 12 filings have gradually increased year-over-year and have now approached levels unseen since 2012— although the filings are still substantially below levels seen prior to 1998.

Farm Bankruptcy

Chapter 12 bankruptcy, more commonly referred to as farm bankruptcy, is a bankruptcy procedure where family farmers or family fishermen can restructure their debts to be repaid over a period of three to five years, conditional on income and debt limit requirements being met. The chapter was created in 1986 as a response to the 1980’s Farm Crisis, to serve as a bankruptcy option for farmers to retain their farm.

The farming debt limit for chapter 12 was recently increased to $10 million with the passage of the Family Farmer Relief Act, which was signed into law on August 23, 2019. The prior debt limit was $4.4 million as of April 1, 2019. The effects of the increased debt limits have been muted so far—less than 1% of all farmers that have filed for chapter 12 since the increase have had debts larger than the old limit. However, the increase is likely to have long- term implications, as the average debt load of filers has been steadily increasing.

Reasons for Filing Chapter 12

In general, a farmer is likely to file for bankruptcy if their current cash flow does not meet their current debt obligations. This situation usually arises not from one specific event, but from a series of events that slowly erodes a farmer’s equity and places them in an insolvent position. Chapter 12 allows the farmer to continue their operation while restructuring their debts by proposing a payment plan over the course of three to five years (although certain long- term debts can be repaid over a longer horizon). Successful completion of a bankruptcy filing leads to the discharge of unsecured debts for the debtor. One of the benefits of a chapter 12 procedure is that it allows a debtor to cram down secured debts to the current value of its collateral, as unsecured debt is dischargeable in a successful bankruptcy filing. While chapters 11 and 13 also allow for a cram down, those chapters are prohibited for cramming down mortgages, a limitation that chapter 12 does not share. With over 80% of a farmer’s assets tied up in agricultural land, a chapter 12 cram down can be extremely useful for farmers in areas of declining land values that previously took on debt to finance the purchase of their land as reclassifying secured debt to unsecured debt. Declines in agricultural land values are thus a leading cause for filing a bankruptcy, although negative income shocks, increased debt costs, and unexpected costs also contribute to bankruptcy filings.

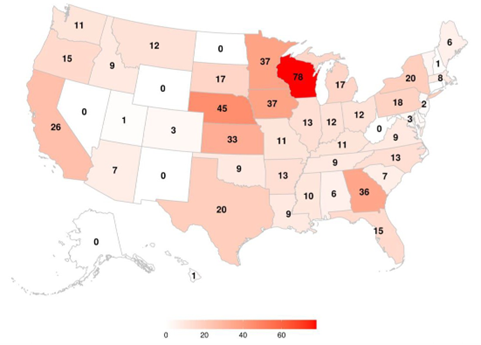

While there has been an increase in chapter 12 filings since 2014, certain areas in the United States have felt more financial stress in agriculture than other areas. Over the past year the upper Midwest has seen a considerable increase in chapter 12 filings, with Wisconsin leading the nation in chapter 12 bankruptcies. The main culprit for farm bankruptcies in Wisconsin has been the lagging dairy sector, which has suffered low commodity prices due to overproduction in the industry. For other areas in the upper Midwest, like Kansas in particular, the stagnant or declining agricultural land markets that have resulted from multiple years of declining farm income—a trend that has recently been exacerbated by the trade war with China— have contributed to increased bankruptcies.

Farm Income

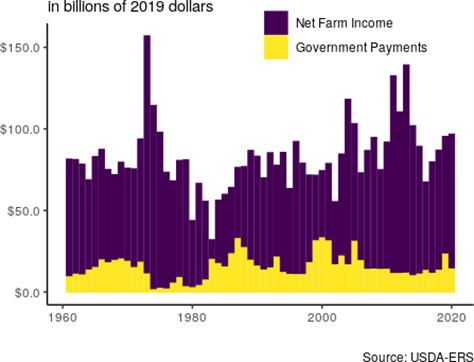

Since 2016, net farm income has been slowly creeping up nationally, but has yet to return to the decade’s early boom period. Market Facility Program (MFP) payments began impacting net farm income measures in 2018. The program was meant as a one-time payment to compensate cotton, corn, dairy, hogs, sorghum, soybeans, and wheat producers from foreign retaliatory tariffs. However, this program was again enacted in 2019 (to be paid over 2019 and 2020) due to the elongated trade war, and the scope of covered commodities was greatly increased. Uncertainty surrounding a major export market for agricultural producers has greatly affected future expectations in farm incomes, which has been reflected in land markets.

Of the $83.78 billion in net farm income for 2018, about $13.67 billion were direct government payments, a majority of that from MFP. Current estimates for the 2019 and 2020 net farm incomes are $93.56 billion and $96.67 billion respectively, with substantial support from government payments ($23.66 billion and $14.98 billion). While MFP payments certainly buoyed current cash flow, the program is still only designed as a temporary measure. The degree of future measures to support net farm income is unclear, despite ongoing global factors affecting farm, including the COVID-19 pandemic. Government measures to counteract the effects of COVID-19, such as the Coronavirus Food Assistance Program (CFAP), will provide up to $16 billion in direct payments, which has yet to be accounted for in the USDA ERS estimates of net farm income. The uncertainty in how these payments will be distributed makes it hard to gauge how much government payments can stave off the current upward trend in bankruptcy filings.