Farmers and Ranchers React to Higher Rates

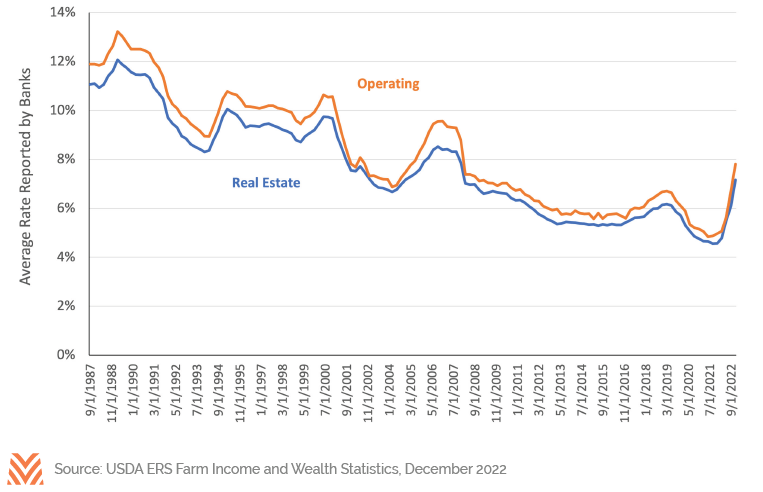

Farmers and ranchers are processing a new interest rate regime that has been increasing at the fastest pace since the 1970s. In 2022, the average interest rate reported by banks in the Tenth Federal Reserve district (Wyoming, Colorado, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, and parts of New Mexico and Missouri) rose by more than 2.50 percentage points on real estate loans and almost 3.00 percentage points on operating debt. Those rates of increase are nearly double the prior high-water mark for the series going back 35 years. Many farmers and ranchers locked in historically-low interest rates between 2020 and 2022, minimizing interest rate expenses on real estate and some operating debt for years. However, some farm debt resets annually, exposing borrowers to the higher rate environment in 2023. Additionally, borrowers looking for refinancing or new mortgage debt will face higher principal and interest payment levels than in recent experience.

Borrower Response

Debt-seekers can pull three big levers in this elevated rate environment (and some farmers and ranchers will pull multiple levers simultaneously). First and most simply, borrowers can pay more in principal and interest payments in order to access needed capital, but this can be costly. A 30-year mortgage for a $1 million loan at a 4% interest rate would have an annual payment of around $58,000. The same loan at a 7% interest rate would have an annual payment of around $81,000, or roughly a 40% increase in yearly debt requirements. This difference could be small relative to the operation’s overall balance sheet and income statement, but it could also be a big hurdle for smaller operators.

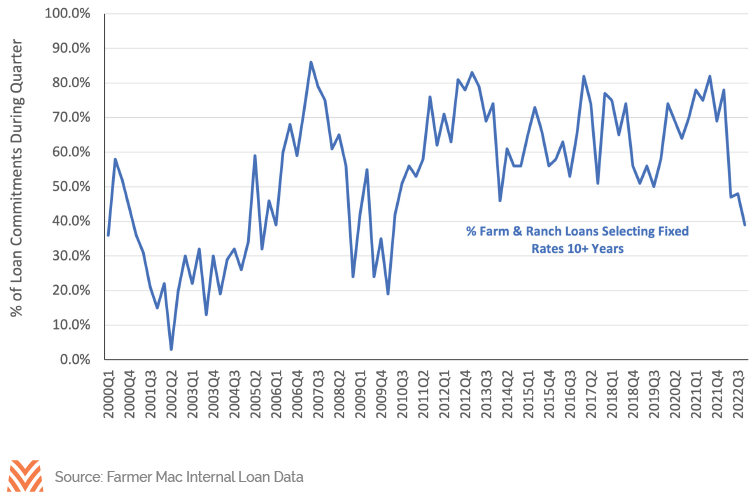

Second, borrowers might try to find savings via different loan products. If short-term debt is costly due to the Federal Reserve’s Federal Fund Rate target, a borrower may look longer out on the yield curve for some savings. If long term rates are also elevated, a borrower can find some middle ground in a product that locks in the rate today but will change in three, five, or ten years and may offer some savings and optionality for the borrower. Indeed, during times of low rates and a flat interest rate curve, loans trading in the secondary market tend to choose a high percentage of long-term fixed rates (see the figure below).

Third, borrowers can adjust how much they borrow. If a farm operator can cash flow $80,000 in annual principal and interest payments for their real estate debt and they have $2 million in farm real estate to pledge as collateral, a 4% interest rate environment allows them to borrow nearly $1.4 million or a 70% loan-to-value ratio. In a 7% interest rate environment, that same operation would likely only be able to afford a $1 million loan or a 50% loan-to-value ratio. In other words, for a borrower to maintain the same cash flow ratios as they could in a low-interest rate environment, the higher mortgage interest payments would require them to reduce the possible loan balance by 28%. Lenders, too, can see collateral requirements increase during rising rates. Lenders are not necessarily tightening standards, but loan-to-values naturally fall when borrowers’ cash flows cover a smaller loan amount.

Lender Response

Lenders can also react to the rising rate environment in numerous ways. First, lenders may ensure that borrowers can access loan optionality. Annual operating debt has a natural optionality because of the renewal process, but some longerterm real estate mortgages have prepayment penalties or yield maintenance provisions that can prevent borrowers from refinancing when rates come back down. Lenders can help borrowers maximize their future flexibility with transparency and education on product selection and prepayment optionality. Second, lenders can monitor the rate environment and look for temporary declines. Like most economic series, interest rates never move in a straight line. There are likely periods of volatility in which rates decline and give windows of opportunity for lenders and borrowers that are paying attention. Finally, lenders can keep in constant contact with their customers on capital needs; if rates start to recede, farmers and ranchers who are prepared and ready to move will be in an excellent position to quickly close on loans at lower rates.

No matter the interest rate environment, farming is a capital-intensive business. Debt will continue to be a part of the capital stack for America’s farmers and ranchers, and ag lenders will continue to provide access to capital at the best rates and terms the market can offer. For 2023, at least, robust farm incomes and elevated working capital give ag borrowers solid footing to handle this dynamic interest rate environment.