Interview: Farmland Values in a Rising Rate Environment

FARMER MAC: Do you expect farmland values to change in 2022 because of increases in the Federal Reserve’s interest rates?

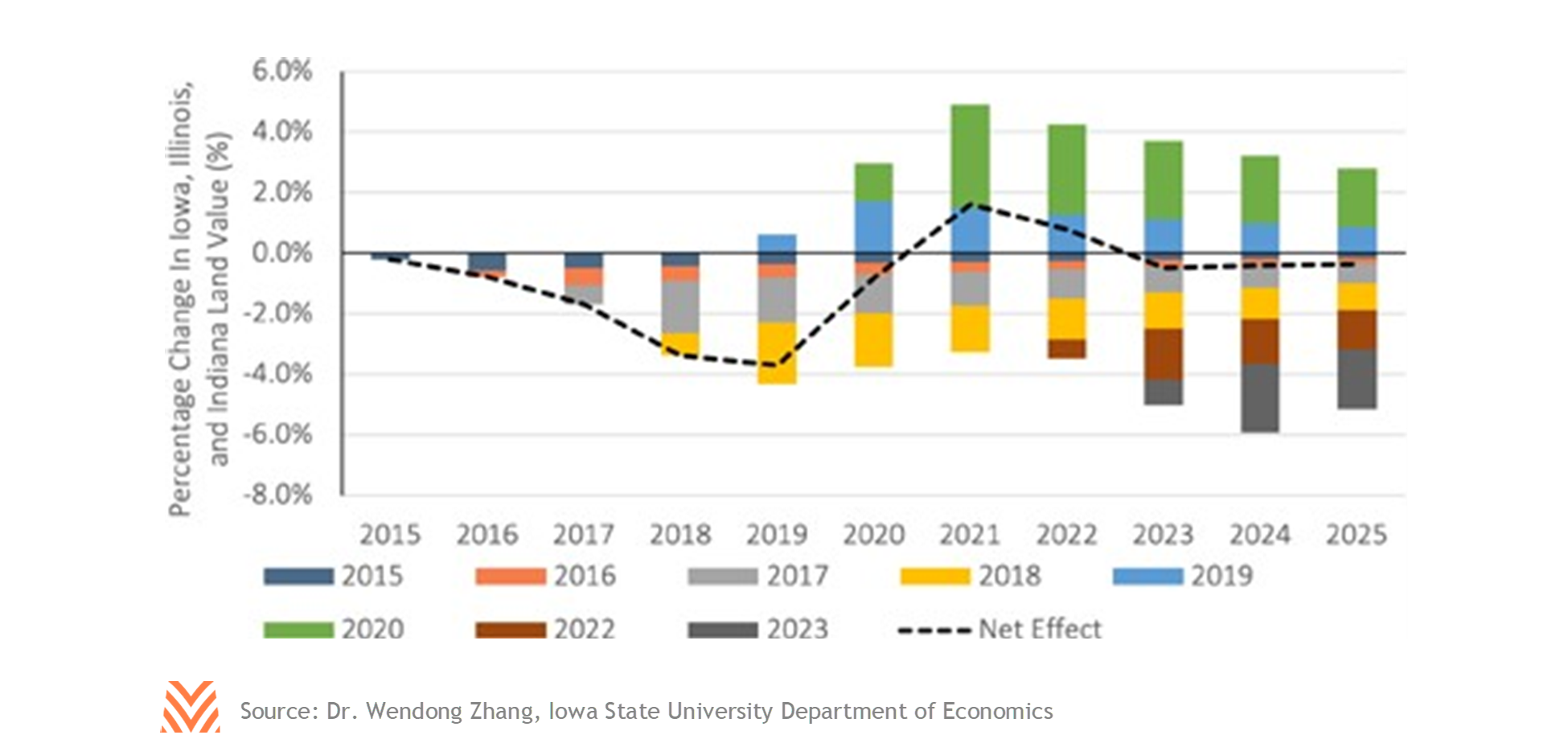

Dr. Zhang: There are definitely downward pressures because of interest rate hikes. Farmland value roughly can be thought of as income divided by interest rate. Our model shows that the downward pressure imposed through the projected three hikes this year probably won’t be enough to offset all the substantial cuts over the last few years, especially the March 2020 rate cuts. For the monetary policy we are likely to see, the interest rate environment in 2022 is still a net supporting environment. But this support may not be as strong as it would have been without rate hikes, and we probably will see downward pressure starting late 2023.

How long after the last rate hike do you think it would take for producers to feel the full brunt of that on their land values?

Our model projects three hikes in 2022 and four more in 2023; we foresee modest downward pressure in 2023, with more in 2024 and 2025. The bigger question is agricultural incomes. When we are looking at incomes for 2022, we do predict that projected income will decline compared to 2021, especially if there are rising input costs and if ad hoc government aid slows down. Looking at the export market, there are some headwinds, especially those coming from China. So, there are some downward pressures, but we still anticipate significant profitability margins, especially if the growers take advantage of before-harvest marketing opportunities. If you look at the Iowa Land Value Survey, a lot of the respondents are expecting around 10% growth this year. But yes, the interest rate hikes definitely impose downward pressure, in two ways: they raise the cost of financing, and they make other investment alternatives, like bonds, a little more attractive due to their higher rate of return.

Given typical fluctuations in agricultural incomes: over the next five years, will monetary policy or will agricultural incomes have a bigger influence on total land value growth or decline?

Currently, interest rates are still very low, and even with the high inflation we’re experiencing now, all the signals from the Federal Reserve seem to show that they are taking a slower and modest hike pace. Fluctuation in farm incomes probably will play a bigger role. In general, when there is a 10% change in gross income, you will see the farmland market move four or five percent in the same direction over the following two years. Suppose we see an increase in farming income of 20%. Then, two years later, we’ll see about a 10% increase in land values. Another interesting point looking at this is that the farmland supply is tight, but farmland of different quality and land with alternative characteristics could fare differently. So, I would expect the higher quality land will hold fairly strong and probably show strengths while non-tillable land, especially if lacking hunting and recreational potential, probably will feel more downward pressure.

Are the changes in land values from agricultural income over the last two years greater than potential impacts from the proposed interest rate hikes in your model?

In the immediate short term, this is probably true. We’re seeing farm income starting to show significant increases since 2020, but land markets didn’t respond drastically until the middle of 2021. That’s a lagged response to the income surge, but we anticipate those gains to be capitalized into 2022 land values. Monetary policy is very important, but it takes over a decade to be fully absorbed in the market. It’s often the unexpected, drastic move that will cause significant movement in the real estate market.

Why is it that monetary policy takes so long to be absorbed in farmland markets?

It’s not the case that everyone goes out to get a farmland loan at the same time, so you don’t feel the rate changes immediately. You don’t necessarily feel even the rent changes because those are negotiated only once or twice a year. You could also have a flex lease or some other arrangement that takes some time to be fully absorbed into the market. In general, monetary policy will need a long time to be realized in competing asset returns to be fully felt by the general economy and the agricultural economy.

Your previous work shows that some states, like Illinois, Indiana, and Iowa, absorb changes in monetary policy more quickly than some other regions. What drives differences in how quickly regions respond to interest rate changes?

As I mentioned before, we think of land values as income divided by interest rate. The relative significance of the interest rate is different. If you’re looking at the Dakotas, whether you have energy development potential matters a lot. If you’re in the western U.S. and have water rates, that will be much more important than monetary policy movement. When you have more sources of income beyond just crop income it’s harder for producers and investors to figure out how much these effects should be in the market. If we look at the states you mention, the more significant impact is because when people think about farmland, they think about these states. When you have less complicated income sources, the capitalization is easy to think about. When you have diverse values coming from urbanization, energy, water rights, and other factors (like pasture or recreational potential), that makes it harder to figure out exactly how much should be reflected in values.

Does that mean that farming- dependent counties will see changes in monetary policy absorbed more quickly into farmland values?

Not necessarily. For my dissertation, I looked at western Ohio farmland values, so we looked to see how urban influence impacted nearby farm values. You see that nonfarm factors, such as urban influence, matter a lot. During the 2007 residential housing market bust, the farmland market dropped significantly for these para-urban parcels. This wasn’t because their productivity value dropped, but because their urban premiums were cut in half. So, to the extent that the residential housing market responds quicker to interest rate hikes, that will be reflected in nearby farmland parcels where a portion of their value is due to urban premiums.

Is there anything that you think is missing or under-covered from the national conversation around farmland values?

We’ve noticed in the recent land value surge is not only due to producers; it’s also due to investors. How the interest rates affect returns on alternative assets such as stock and bonds will affect the demand from investors for farmland. The more direct and volatile impact of interest rate changes on stocks and bonds could have unique pressures on investor interest for farmland. Another thing impacting investor influence is state-level variations in corporate land ownership. There are state- level variations in foreign land ownership and registration requirements. These variations can help explain why certain regions have more investor activity than others. It’s also important to understand that these investors view land as part of an investment portfolio in addition to the agricultural returns. In the Midwest, a quarter to a third of land is bought by these types of buyers. This is a broad definition that includes people like retired farmers. In the Iowa Land Ownership Survey, 19% of these individuals owned the land for long-term investment, 29% for family and sentimental reasons, and about half owned for its agricultural income.

Second, another astonishing statistic from the survey is that 81 to 82% of the land in Iowa is fully paid for. A lot of the lenders who went through the 1980 farm crisis have started to worry about the farmland market collapsing. The current signal doesn’t point to this alarming future, in part because the interest rate levels are still low and the steps indicated now are not as drastic as in the 1980s. On top of that, the sector overall is far less leveraged compared to the late 70s and early 80s. On a broad spectrum, I think it’s way less risky compared to what we saw during the 1980s.