Rising Retail Prices May Not Impact Producer Profits

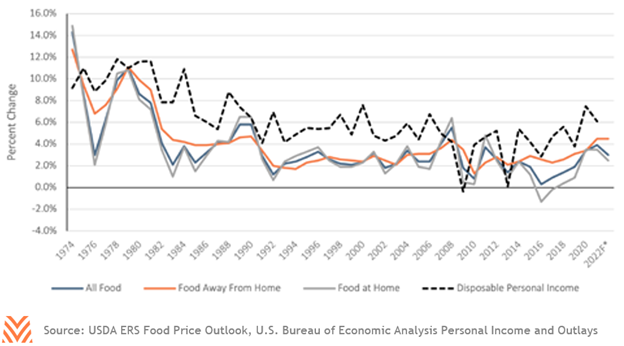

Over the past year, Americans have noticed sharp increases in many prices at the grocery store. The USDA Economic Research Service (ERS) estimates that the consumer price index (CPI) for beef and veal rose 9.6% in 2020 and 9.3% in 2021. The rise in the price of meat has dominated coverage around food price inflation, but the broader picture is more muted. Fruits and vegetables, bakery products, fats and oils, and other non-animal products showed growth that was closer to historic averages. The figure below shows the history and current 2022 projections for CPI growth for food in 2022. In historic terms, the recent growth in food costs is not unusual. Consumers saw a similar period of price growth across a wide range of commodities throughout the commodity supercycle, including double-digit annual growth for meats.

What matters more for consumers is the cost of food relative to income. Through 2020 and 2021, robust government support helped drive American disposable income higher, lessening the impact of price increases for food. However, recent evidence suggests that recent food price increases could be outpacing wage growth. Over the second half of 2021, the Bureau of Labor Statistics estimated that the CPI for food grew faster than average hourly earnings five out of six months. This is also not something without recent historic comparison; food cost growth outpaced wage growth during the 2008 financial crisis, and even outpaced wage growth for 18 months during the early stage of the commodity supercycle.

The question producers and lenders may be asking is whether they should anticipate more months of food price growth that eclipses wage growth. Farmers and ranchers have seen many input cost increases, as inputs like anhydrous ammonia are three times as expensive as they were in 2020. Indices for trucking costs are at historic levels. These and other sharp input cost increases seem to conflict with the relatively muted total increases in 2022 retail food price growth forecast by entities like the ERS. So, what does drive retail price increases?

Energy

Literature on retail food prices finds that changes are often driven by energy-related impacts on commodity prices or higher energy costs in the food marketing system. These effects are generally more influential for food consumed at home than away from home. One analysis by the ERS found that a 10% increase in diesel prices was associated with a 2.0 to 2.8% increase in wholesale produce costs. The influence of energy is so extreme that, in their calculations of food price inflation, many of the USDA’s CPI forecasts use energy prices as the only input.

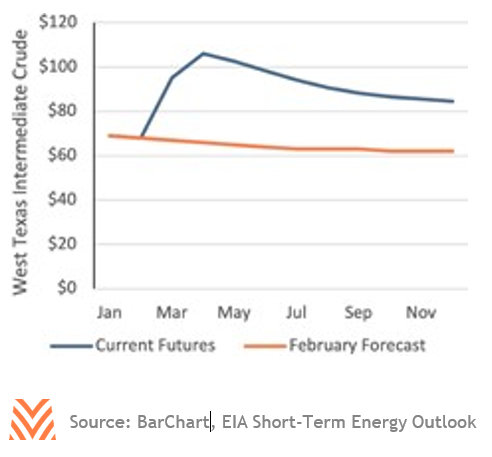

The geopolitical events of early 2022 have made forecasting the net impact on retail activity difficult. An early 2022 February forecast by the U.S. Energy Information Administration forecast that energy prices would subside starting in Q1 2022 as global production of crude continued to rise. This is now out of alignment with current futures markets. The figure below shows the February EIA forecasts compared to the March 1 futures market for West Texas Intermediate crude oil. While there is still an unprecedented amount of uncertainty in the energy markets, the extreme increases in energy prices are likely to cause sharp upward revisions in CPI projections, especially for food consumed at home.

Labor

Despite the importance of energy in forecasting food price inflation, labor represents a far greater share of total retail food costs. The figure below shows the share of total costs by industry group for food consumed at and away from home in 2019. From this, we see that farming-related costs are a negligible portion of the total cost in food production and distribution. Even transportation- related costs make up a relatively small share of the total. Most of the costs fall during food processing or distribution to the consumer through retail outlets and food places like restaurants. The USDA estimates that in 2019, 45% of every dollar spent on food at home went towards salary and benefit costs, while 58% of food away from home did.

What this means for consumers is that changes in labor costs have a strong impact on what consumers pay at a grocery store or restaurant. In 2021, employment cost indexes found that compensation of food service workers rose 6.6% and 5.4% for retail workers like grocery store personnel. However, the private sector anticipates lower wage cost increases in 2022. A January survey on salary and budgets by The Conference Board found that respondents anticipated a median total salary increase of 3.5% in 2022. While this is above historic averages, this more modest growth would mean less pressure coming from labor expenses.

Elasticity

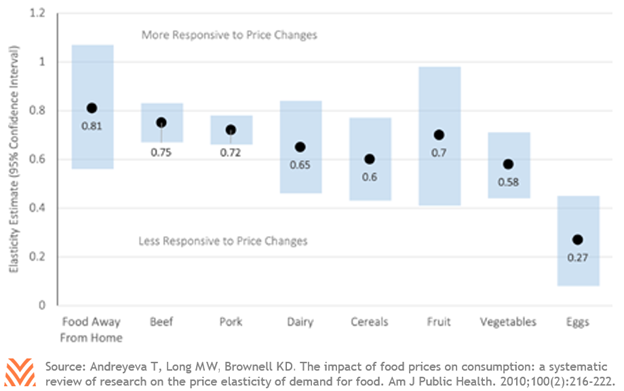

These factors tell us that retail food prices are likely to feel pressure in 2022, but they do not tell us how consumers will react. If food prices increase but consumers don’t alter their purchasing behavior, the impact on producers will be muted. Prior analyses have found that periods of high commodity prices are correlated with lower meat consumption in the United States. But the magnitude of this response is important. If consumers do not substantially curtail their consumption in high price environments, then producers may see limited impacts on total sales.

The elasticity of food in America—the change in how much of a food consumers buy in response to a change in price—is a topic with a long body of research. In general, there is a broad consensus that most food consumption in the U.S. is not responsive to price increases (though there are differences across food groups). The figure below shows the mean elasticity and confidence intervals for select food groups from a meta-analysis of this research. The analysis suggests that a 10% increase in the cost of food away from home would lead to an 8.1% decline in the quantity of that food consumed. Conversely, it suggests that a 10% increase in the cost of eggs will only lead to a 2.7% decline in consumption. In general, beef and food away from home are more responsive to prices, while staple goods respond less to price changes.

While rising food costs are an important consideration for Americans, they may not be as relevant to American producers. Current projections are that food price inflation will be elevated, but in line with prior periods of food price growth. Costs of production that occur on the farm are often a negligible portion of total food costs, and projected increases in farm expenses in 2022 are unlikely to have material impacts on consumer decision-making. Retail prices will be more sensitive to changes in energy and labor costs, but those price changes tend to have muted impacts on Americans’ buying behavior. Buying a steak sandwich might feel like a luxury purchase in 2022, but the net effect to farmers and ranchers is likely far less than the price hikes suggest.