The Global Economy and Ag Trade

Agricultural prices are predominantly driven by exports. Exports led the price surges in the 1970s, 1990s, and late 2000s. These spikes were caused by a series of macroeconomic factors in addition to changes in agricultural production. While these periods are not identical, they shared many macroeconomic themes: a strong economic environment and a depreciating U.S. dollar that led to export growth. With the globe in a recession, many of these same factors will now be working in the opposite direction, suppressing agricultural exports and profitability through the downturn.

Growth in Major Importers

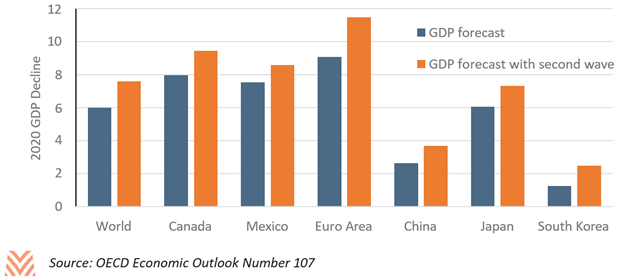

Global growth is important to U.S. agriculture because it increases disposable income and creates new markets for American products. Historically, negative or slow growth has led to decreased demand for animal proteins and a reduced need for crops through impacts on feed. Globally, the OECD forecasts that GDP growth will be negative 6%, or almost negative 8% if a substantive second wave of COVID-19 cases emerge.

The emerging economic downturn will not be even across our major agricultural markets. Canada and Mexico accounted for almost 30% of U.S. agricultural exports in 2019 and are both forecast to see sharper declines in GDP growth than the global average. The Eurozone represents another 9% of exports and will see some the sharpest declines in the world. Spain, France, and Italy are all forecast to see declines of between 11% and 14%.

Impacts are less severe to our major partners in Asia. While Chinese growth expectations have fallen significantly, they are forecast to see only a mild contraction in 2020. South Korea’s ability to curb the spread of infection has also resulted in lower forecast GDP declines. While Japan has also seen lower case counts, the Japanese economy has been slower in recent years, and so is forecast to see a greater contraction in 2020.

This regional variation will place unique pressure depending on the commodities these countries import. In 2020, almost 15% of the goods by value going to hard-hit Europe were almonds. Canada imported more fresh fruits and vegetables, while Mexico’s top U.S. imports were corn and soybeans. Across Asian nations with smaller forecast GDP declines, beef and pork are top exports. This could provide some insulation for animal products, though they will face more headwinds from GDP declines in emerging markets.

Strength of the US Dollar

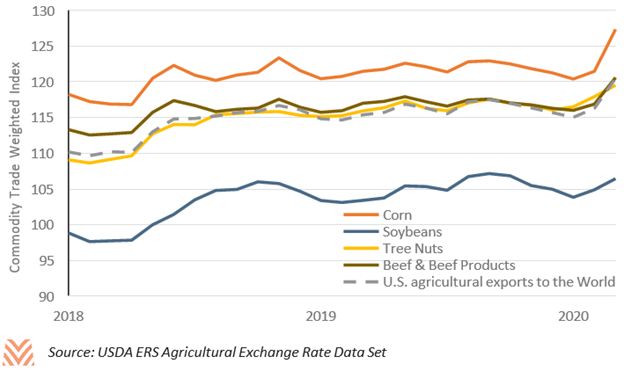

A stronger U.S. dollar reduces the competitiveness of American commodities. Since March, the U.S. dollar has appreciated against a basket of currencies. This appreciation will have disparate impacts on commodities based off how the U.S. dollar has appreciated against the currencies of countries who either import or export that good. For corn, the dollar has surged against the Mexican peso and Brazilian real in March, weakening U.S. competitiveness. Tree nuts have seen less change in their competitiveness since importers like the E.U. have seen less change relative to the dollar.

Over the near term, forecasts indicate that currencies for major agricultural exporters like Russia and Brazil will continue to depreciate relative to the U.S. dollar. Weak oil prices will continue to place pressure on the ruble and are unlikely to change over the short term. In Brazil, the pandemic accentuated pervasive structural issues that have caused depreciation against the dollar. However, forecasts are stable for major dairy and meat producing regions like the European Union or New Zealand. This could provide some stability for animals and animal products while weighing on major cash grains.

Other Factors

Energy costs are closely tied with U.S. agriculture costs. The largest impact stems from biofuels: as biofuel prices rise, the profitability and use of agricultural products like corn or sugar cane increases. However, low energy costs also lower farm expenses and prices for commodities like wheat and soybeans. As mentioned above, petrostates like Russia have currencies that are closely linked to oil prices. As oil prices decline, those nations’ currencies depreciate, increasing their competitiveness against American goods. Through 2021, the U.S. Energy Information Administration forecasts that the price of WTI crude will not return to pre-pandemic levels.

There are myriad other ways that the global economy could influence American agricultural exports. Population growth is the most important driver of total exports, and this growth slows during recession events. The costs of government response to COVID-19 could leave nations unable to fully fund agricultural research, which could lead to lower productivity in the future. However, low inflation and robust government policies may partially offset anticipated declines.

U.S. farmers are closely intertwined with the global economy, even when not accounting for foreign agricultural production. Through at least 2021, producers will have to work in an environment with contracting economies, low oil prices, and a stronger U.S. dollar. However, not all commodities or markets will be impacted the same. Global pressures will be strongest for commodities like corn and wheat. Animal proteins and consumer-oriented goods are typically most at risk during downturns but may see some support due to where those commodities are produced and purchased. The outlook for 2020 may be poor, but if producers can get through the current growing season, many global factors should once again be working in their favor for the next crop marketing year.