Water, Water (Almost) Everywhere in the Southwest

Water Deliverance in California

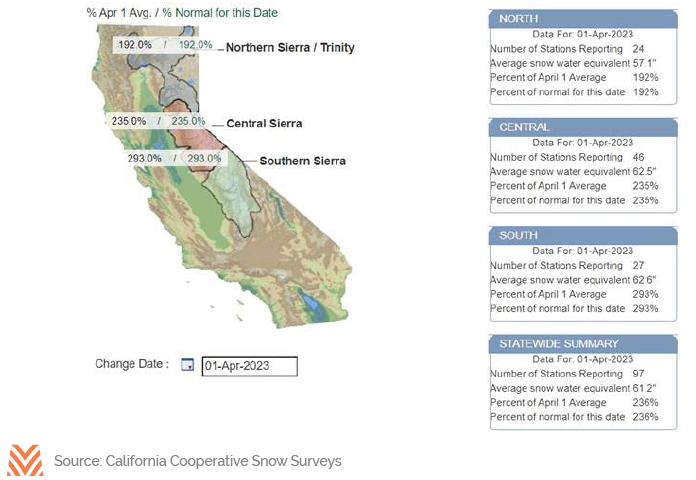

After three years of intensifying drought, California finally received some sorely needed rainfall this winter. In some regions in the state, December and January storms brought record rainfall. While the rain ultimately provides only a small amount of direct relief in replenishing soil moisture, these precipitation events have had a big impact on state snowpack levels. California relies on melting snowpack each spring to replenish aquifer water levels, making snowpack a closely watched benchmark for residential and agricultural users. Statewide snowpack levels surpassed 237% of historical average this winter, reaching the highest level on record.

The surge in precipitation this winter has sparked optimism among agricultural and urban users alike. Reservoirs throughout the state were significantly depleted by several consecutive years of drought leading up to 2023 but now are expected to reach capacity this year. This is a positive shift for Lake Shasta, the largest reservoir in California, where water levels had dropped to 34% of capacity by the end of 2022. The winter precipitation has already lifted Lake Shasta’s water level to 97% of the reservoir’s capacity and will hover near full-capacity as the snowpack melts this spring.

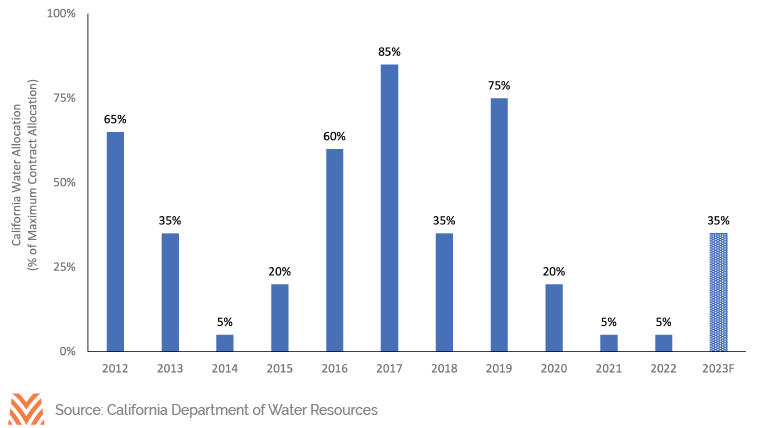

This year’s rebound in the snowpack should directly benefit California’s agricultural sector. The California state water allocation for 2023 was raised to 35% in February, the highest level since 2019. After two consecutive years of minimum allocations, growers are welcoming the projected increase this year. The current allocation of 35% is unlikely to fully satiate demand for irrigation water, but there is reason to believe this allocation may increase, as they historically have been raised once a final water inventory is established in the spring.

The rebound in snowpack levels doesn’t guarantee an end to tight water supplies in California. The last several years of drought conditions have led to increased demand to pump irrigation water from the ground. The Sustainable Groundwater Management Act Groundwater (SGMA) regulates groundwater usage to long-term sustainable levels. However, the gradual transition to sustainable groundwater pumping has allowed groundwater levels to decline upwards of 25 feet over the last year in some agricultural districts. Replenishing these underground water supplies will likely require more time than refilling a reservoir. Still, historic snowpack and full reservoirs should help recharge aquifer levels and limit groundwater demand in the near-term.

U.S. Southwest

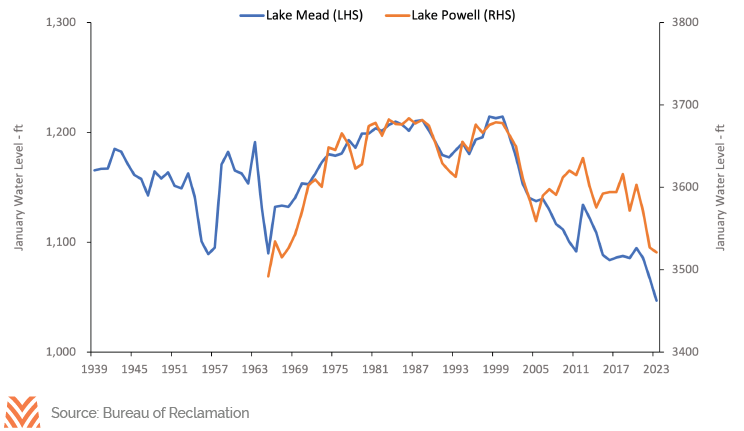

While the drought situation has improved in California, the water situation remains precarious in Arizona and other Southwest states. The two largest reservoirs in the U.S. are Lake Powell and Lake Mead. Both reservoirs currently sit at the lowest water level since their creation decades ago. These reservoirs are linked, as Lake Mead is filled in part by runoff from Lake Powell. Water levels in these reservoirs have trended moderately lower for decades as agricultural use grew and the population in the U.S. Southwest expanded. And in the last several years, drought has accelerated reservoir-level decline.

In response to the broad decline in water availability along the Colorado River, the Department of Interior declared a Tier 2 water shortage (i.e., a measure of severity established by drought contingency plans) in August 2022. The designation resulted in the loss of up to four million feet of water allocation for seven Colorado River basin states. Arizona faces the largest reduction and will receive as much as 21% less water in 2023 than the historical agreement allocates to the state.

The importance of water conservation continues to grow for Arizona agricultural producers. Currently, nearly three-quarters of Arizona water use is related to agricultural production. Much of this was historically sourced from the Colorado River and related reservoirs. Many producers have been able to pivot to ground-water irrigation in the face of declining reservoir levels. However, a drop in aquifer levels shows this strategy has limits as well.

There is reason to be optimistic that the Tier 2 water shortage won’t be elevated to a Tier 3 designation by officials this year, as snowpack levels in the Upper Colorado Basin entered May at 150% of the historical average and were already above the average annual peak. However, it remains unclear if this factor alone will be enough for officials to downgrade the water shortage to Tier 1, as replenishment of the depleted reservoirs is expected to require consecutive years of above-average precipitation. In the near term, farmers in the U.S. Southwest can expect to have to continue navigating limited water supplies amid greater demand from agricultural and non-agricultural users.

Livestock Impacts

The spread of drought conditions from the U.S. Southwest to the Southern Plains has received comparatively less news coverage but is directly impacting the agricultural sector. Notably, cattle producers have been challenged by the degradation of pasture conditions due to a lack of rainfall. Over half of the U.S. cattle herd is currently located in drought-affected areas. This is down slightly from the peak of 76% in November, which was the highest level since late-2012. Still, the USDA rates most pasture conditions as fair or poor, leading producers to rely more heavily on hay and other feedstuffs. Hay prices have increased over 20% year-over-year, leading many producers to cull cattle instead.

The U.S. cattle herd has historically cycled through periods of expansion and contraction, but the current situation is relatively unique in size and timing. Total U.S. cattle and calves declined by 2.8 million in January relative to last year. This was the largest decline since 1989. At the same time, retail beef prices hovered near record levels for much of the last three years, while beef exports set a new record in 2022. Processors benefitted most from the robust demand for U.S. beef by capturing record margins while farm level prices stayed relatively low. Still, drought conditions and the corresponding rise in feed prices have limited cattle producers’ ability to expand.

For livestock and crop producers in drought-affected areas, farm profitability has likely lagged behind other agricultural producers this past year. Higher water costs compounded the already rising production expenses for many growers. Producers unable to source irrigation water experienced lower crop yields and revenues. Crop insurance and ad hoc payments provided moderate relief to some producers. The impact on farm finances can last for several years, though, including after the drought has ended. Rebuilding livestock inventories and replanting permanent crops that were pulled out during the drought will both take time. The predicted end to the La Niña weather pattern this spring is welcomed news for producers across the U.S. Southwest. Future droughts are likely, though, and understanding this ongoing risk is increasingly vital within the agricultural sector.