Will High Prices Hinder USDA’s CRP Goal?

AgWeb

By: Sara Schafer

CRP acres often follow market forces, according to research from Farmer Mac. As such, today’s high cash grain prices may dissuade producers from enrolling acreage in CRP programs.

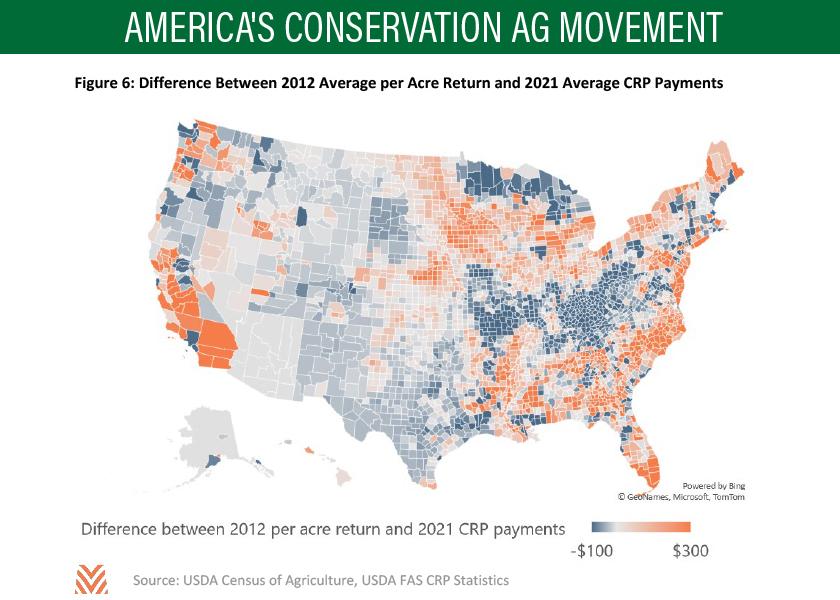

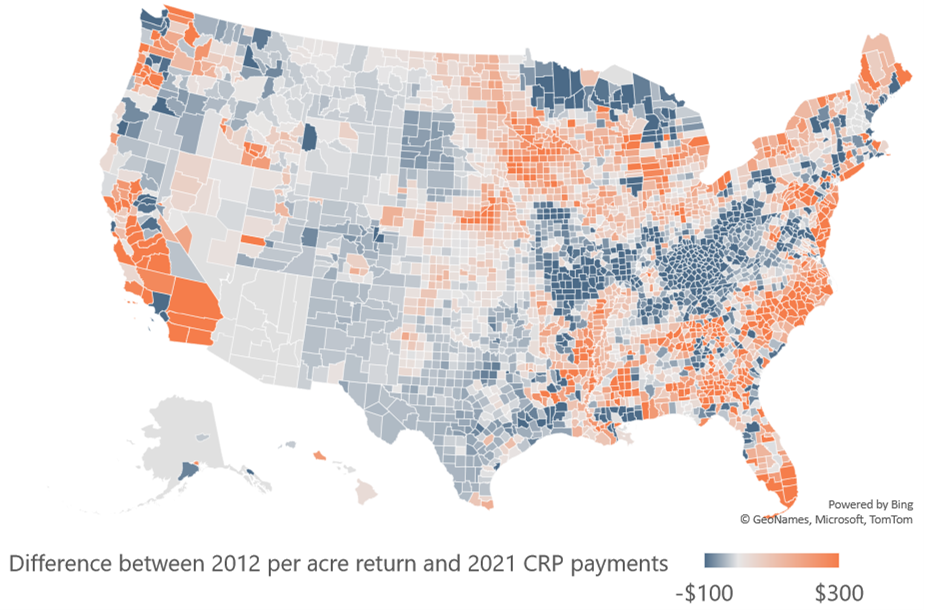

(Source: USDA Census of Agriculture, USDA FAS CRP Statistics)

In late April, USDA announced an expanded Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), which offers annual payments to producers in exchange for their removing environmentally sensitive land from production for up to 15 years. New acres enrolled will garner higher payment rates, new incentives and a more targeted focus on the program’s role in climate change mitigation, according to USDA.

In 2021, CRP is capped at 25 million acres, and currently 20.8 million acres are enrolled. The cap will gradually increase to 27 million acres by 2023. (FSA opened the general signup in January 2021 and extended the original deadline to July 23, 2021, to enable producers to consider FSA’s new improvements to the program.)

But will the program attract all those acres? CRP acres often follow market forces, according to research from Farmer Mac. As such, today’s high cash grain prices and strong crop production returns may dissuade producers from enrolling acreage in CRP programs.

This will leave farmers asking vital questions, says Jackson Takach, chief economist for Farmer Mac. These include: Can I make more money growing something this year? Or, is it more economical for me to enroll it in CRP for a period of about 10 years?

“It’s very difficult to turn down $6 corn even with that CRP payment, which in some cases is pretty substantive,” Takach says.

Takach and his Farmer Mac team analyzed how the last period of high commodity prices (2012) impacted CRP acres. While there are some differences between the markets in 2012 and today, there are enough similarities in the grains markets to glean some insight, the economists found. They then plotted the results (the difference between the average per acre return in 2012 and 2021 average CRP payments) on a county level:

Source: USDA Census of Agriculture, USDA FAS CRP Statistics

The areas in deep orange may be less likely to sign up for CRP, given current market strengths. However, there are areas (in blue) where CRP payments may be more competitive.

Takach says the research shows USDA may be able to reach its target of CRP acres, though it is unlikely to make great strides in corn and soybean territory.

“In states like Iowa and Illinois, it is hard to beat the economics of growing corn, soybeans and other crops,” he says. “But if you go a little bit farther south into the Southeast and parts of the West and the Northern Plains, it’s actually a pretty good economic deal for farmers to look at that CRP enrollment.”

The regions with the most expiring contracts today, such as around Texas and Montana, are also the ones where the economics of CRP enrollment look good for local producers, Farmer Mac found. This has some minor implications across commodities.

Meanwhile, few acres from the Corn Belt region expired. Many CRP acres expiring in 2020 would have been enrolled around 2010, when sudden increases in corn and soybean prices may have led to fewer enrollments in that region, Takach says. While current market conditions may not entice new CRP enrollments in the Corn Belt, total CRP acres in that area may not decline significantly over the next few years.

“It really depends on how long this commodity mini-boom lasts,” he says. “If it’s into 2022, I think it’ll be hard for people to want to enroll this year in CRP. It’s a very complex story, and I think we’ll learn a lot more as we see what happens towards the back half of 2021.”

Read more from Farmer Mac with their quarterly publication, The Feed.

To View Full Article: Click Here